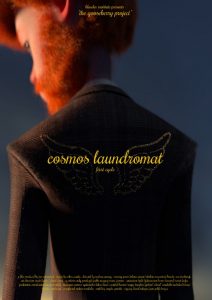

Aside from his charming personality and humor, Hjalti Hjálmarsson is one of the best Blender character animators out there. Last year he joined the Blender Institute team and is currently working on wrapping up Cosmos Laundromat—his most challenging project so far.

Aside from his charming personality and humor, Hjalti Hjálmarsson is one of the best Blender character animators out there. Last year he joined the Blender Institute team and is currently working on wrapping up Cosmos Laundromat—his most challenging project so far.

I was looking for a chance to pick his brain, ever since we’ve been involved in the Gran Dillama short open movie—he animated it, we did the rendering. The following ten questions discuss the secrets of the animation craft, the benefits of Animation Mentor classes he graduated, and valuable insights on what takes to be a master animator.

Marius Iatan: What childhood cartoons do you think left an impact on you as an animator?

Hjalti Hjálmarsson: Growing up I used to binge-watch cartoons. It really didn’t matter what it was, if a cartoon was playing I’d be watching it. I also had the tendency to utterly space out while watching them. Even if someone was calling my name, my mind was deep inside that TV, utterly absorbing every frame. During my childhood The Simspons, Looney Toons and all the classic Disney movies definitely left a mark. For better or worse.

Marius: Do you have a biased perception when watching animation movies? What technicalities are you looking for when seeing a scene?

Hjalti: Story and character are the most important things of any movie but let’s put that aside. These days when I watch animated movies my eyes yearn for good timing and spacing. It’s what separates “good” animation from “great” animation. It can make or break any joke, action or heartfelt moment. Seeing it done properly by talented animators will make your jaw drop and elevates the shot to new heights. It will fill you with inspiration and, more importantly, curiosity. You’ll get that urge to go frame-by-frame over the shot to see how the heck they pulled it off.

Scene from Gooseberry project

Marius: How many hours of research do you do for animating a new type of character? Do you have a ‘white whale’, a character that you feel you’ve never reached perfection in animating?

Hjalti: Depending on the character and deadlines, doing research and tests might take anywhere from a day to perhaps a couple of weeks. There’s sometimes the tendency for project managers to try and skip the “research” phase but in my own experience that’s always a grave mistake. If you don’t put in the effort in the beginning you’ll never get a quality product in the end that reflects the subject matter. As for my “white whale” I always wanted to animate a fun parrot character when I was younger and that itch was pretty much scratched when I got the opportunity a few years ago to create an animated ad-campaign that featured a cute bird. At some point I would love to animate a cat-like character, that’s something I’ve never tried.

Marius: Can you explain the workflow that takes place between different 3D professionals when working on a movie? Where does the animator stand in the production pipeline?

Hjalti: Please note that the answer to this question will vary wildly between projects and studios. A five person studio making a 10 second commercial will work very differently than a feature film studio so I can only answer in a very broad boring way. An animator should understand the story and all the main characters (their goals, fears, flaws, etc). Also a “lead animator” might have already made test animations that the director likes, in order to nail down better how the characters move and act. This will also apply to the “style” of animation, so all the shots will feel consistent. An animator will be assigned a shot that has already been through the layout process so staging of the characters and camera movement should be very clear and approved. The director and/or animation supervisor goes over what is needed from the shot and how it fits within the scene. The animator needs to also talk to the animators assigned to the shot before and after, to make sure that their acting beats will sync up and the cut between the shots will feel natural. The animator usually takes time to plan out the shot, using reference footage and/or thumbnails. He/she then blocks out their shot very rough at first to get feedback on the overall idea. After many many iterations and feedback sessions (often daily) with the director/supervisor the shot is finally polished and ready. After that there might be a secondary animation team that deals with sculpting contact points where needed but that’s usually only for feature films. The shot then goes through the simulation department (hair, cloth, etc) and the lighting department.

Marius: When animating, you sometimes have to cheat in order to stress out some details or get the wanted effect. At this moment we have software that can animate cohorts of characters for crowded scenes. How do you think the software is going to evolve to simplify your work?

Hjalti: Budget and deadlines are inescapable facets of any project and there’s a constant need to strike a balance. When an animator needs to deliver a massive shot with a lot of characters (like a war scene) in a given timeframe he/she needs to figure out what are the most important things they should be working on. Of course they would love to spend the next 10 years of their life going over every single footstep of every single soldier in the shot to make it perfect but the reality is it might be better to just focus on those 3-4 soldiers in the foreground and maybe spend a few hours fixing the most obvious mistakes the simulated “crowd soldiers” are doing in the background. It’s all about making the shot work and how good you can make it will always depend on the time given. Better simulation technology might be very helpful to an animator, depending on the project, but it will never replace the animator. Just like a “pen stroke” Photoshop filter cannot replace an illustration artist. Technology, by definition, is and always will be complimentary to the art form.

Marius: What was the most challenging project you’ve worked for, so far?

Hjalti: I’d have to say the Gooseberry project that I’m working on right now. There are shots in it that are incredibly difficult both when it comes to body mechanics and acting. It can be quite intimidating to take on such shots but it really pushes you as an artist and of course it helps being surrounded by skillful coworkers. I’m very proud of the entire team and I feel we’ve risen to the challenge and are about to deliver something very unique.

Cosmos Laundromat detail

Marius: Could you share your experience with Animation Mentor online course and some of the things you’ve learned?

Hjalti: Animation Mentor was a very challenging experience, in a good way. The cliché you might hear a bit too often is actually very true. You only get out of it what you put into it. If you half-ass it then you’ll come out of it as a sub-par animator with a much lighter wallet. It’s very important that people realize they won’t come out of it as some animation legend that will be guaranteed a job at all the big studios. Learning the craft is a life-long voyage and you’ll always feel like a student with much to learn. During my studies I had great mentors that would go over my work frame-by-frame and give me brutally honest feedback, which was incredibly healthy. You’ll learn to put your ego aside and just do whatever is best for the shot/scene. I also learned about the importance of giving constructive criticism to other students and how it makes you have a keener eye for your own work. Animation schools in general can be very expensive so I always recommend that people start by testing it out first (reading some of the beginner books and applying it) to figure out if this is something that they’re truly interested in. Being enthusiastic about watching cartoons and being enthusiastic about making cartoons are two separate things. If you’ve been animating simple balls bounces and walkcycles for a few months and still feel very passionate about the craft then by all means go for it.

Marius: When 4k will become mainstream, will it mean more work for each character you create?

Hjalti: Yes. There’s no way around it, in any given situation you’re always animating just enough to fool the eye within the medium. For example higher resolution means you’ll have to spend more time getting rid of any weird intersections that might now have been visible otherwise. The character rig might also need to be more detailed (more bones, shapekeys, etc) to give the animator the tools he/she needs. More bones and detailed mesh means heavier rig and way more things to worry about, slowing the entire process down. This is when a balance might need to be found. You want to convey to the audience the feeling of grief with this story about a cute monkey that lost her teddy bear? Well making it work in 4k instead of 1k might mean 12 times the budget and 3 times the production length. If you simply make it work in 1k and then afterwards re-render the shots in 4k you might actually destroy your connection to the audience. A lot of weird things will now be seen in every frame, not the way it was intended. Even if the audience can’t quite put their finger on it something will “feel” weird and their connection to the story will be greatly affected.

View of the laundromat in Cosmos Laundromat

Marius: Are you looking forward to the next wave of VR hardware, or you are yet to be impressed?

Hjalti: From what I’ve seen in latest VR technology I’m very excited to see what projects can be made to fit this medium and how that might affect the craft of animation. I do have some concerns, seeing that there’s usually the tendency to miss the point when it comes to new technology like this one where producers cram existing media into it that was never made for it. I sincerely hope those kind of sub-par cash-grabs won’t taint the market and we’ll see something spectacular come out of it.

Marius: What makes a good animator stand out? What is the ratio between talent and hard work? And how much does his/her enthusiasm account for?

Hjalti: Just like with any craftsmanship, it’s all about practice. The problem with animation is that it also overlaps with many other crafts but it’s very important to start by nailing down the basics. It doesn’t matter how good your acting is if you don’t fully understand arcs or staging. Your final product will be a convergence of all those skills and there’s no way of “cheating” it by taking some magical shortcut. Anyone saying otherwise is trying to sell you something. Remember that the concept of animation isn’t to just “make things move” but give them the illusion of life via the principles of animation. If you don’t understand and/or have the ability to apply those principles in your work then you aren’t animating.